COVID-19 revealed the absolute necessity for a functioning global supply chain, raising flags about the role technology should play in logistics.

COVID-19 kicked global mask production into overdrive, turning them into a daily fixture and serving as a reminder that while many were sheltering at home, global supply chains kept ticking. But supply chains did miss a beat or two, raising flags about the role technology should play in logistics.

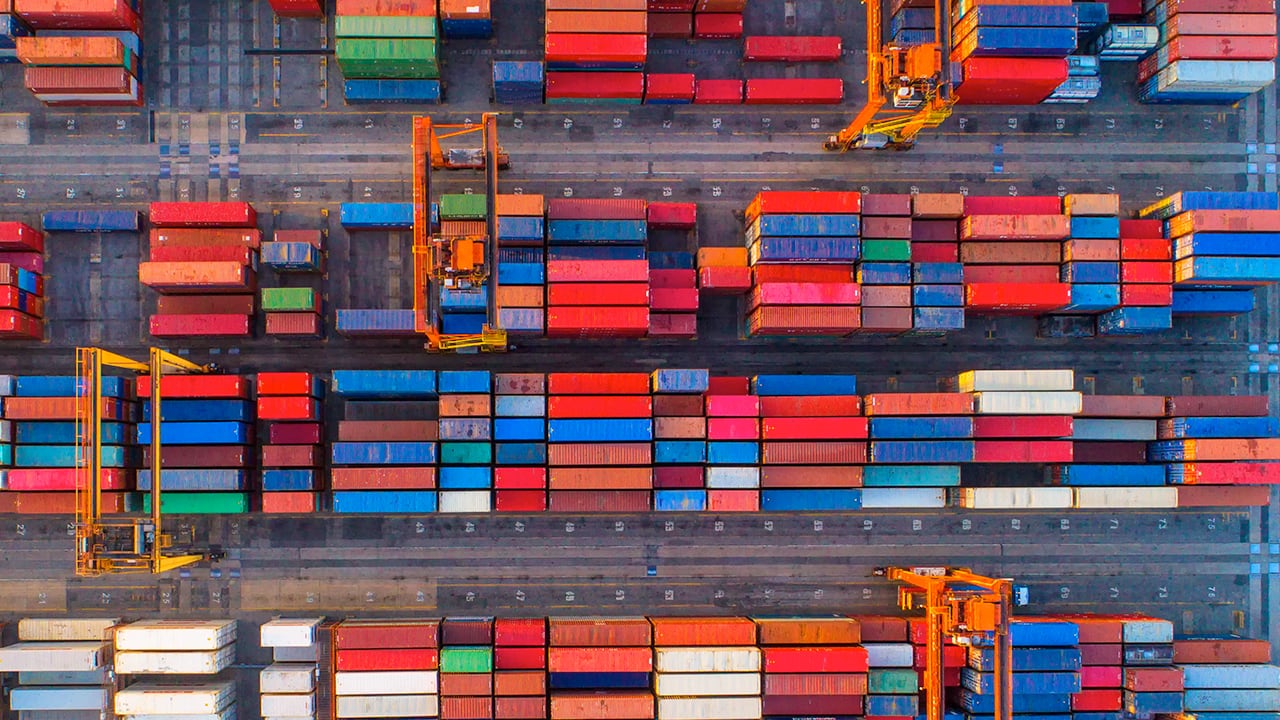

Tech talk usually bypasses the supply chain sector, despite the nearly $20 trillion dollars in annual export of goods, with supply chains bringing food, clothing, computers, and, yes, masks, from factories worldwide to our doorsteps via a global network of airplanes, ships, trucks, and trains. Access to global trade now ranks up there with water, electricity, and internet in the modern Maslowian hierarchy.

Supply chains have thus started to emerge as a major tech focus. If combined, Amazon's warehouse footprint would sprawl across over 25% of Manhattan and, as of 2018; it boasted a fleet of close to 40 airplanes. Alibaba has committed some $14 billion to logistics subsidiary Cainiao. And a vicious war is being waged by the likes of Amazon, Walmart, and Target for home delivery.

Cargo, Meet COVID

Supply chains encountered COVID-19 early. Asian manufacturers typically shut down for the week of Chinese New Year, but in February, China extended the shutdown for over two months. Trucking between Chinese provinces became a bottleneck and the cost of shipping containers out of China plunged, mostly because there was nothing making it to the ports.

By the time Chinese manufacturing revived supply capabilities, the prospect of a long-term global recession impacted demand leading to a whiplash of cancelled or delayed orders. Meanwhile, passenger flights, which carry half of global air cargo, were cancelled en masse, making availability for urgent exports, like masks, a serious challenge. Demand for urgent air cargo was at all-time highs, with prices 400% over February costs, while demand for ocean freight was plummeting.

International shipping wasn't the only victim. Sheltering at home introduced an e-commerce boom also constrained by delivery. By March 17, Amazon stopped accepting new deliveries of non-essential goods from the third-party sellers responsible for over half of all of Amazon's sales. This left tens of thousands of Amazon sellers with inventory but no way to distribute them.

For supply chains of the future, coronavirus has already presented clear challenges. Navigating rapid demand and shipping capability fluctuations became impossible, international freight couldn't adapt fast enough, trucking slowed to a halt, and delivery became a roadblock. The silver lining? It also surfaced the potential opportunities that technology could introduce. And, if they don't emerge, the threat of a shift to near-sourcing could severely impact the sector as a whole.

COVID-19 made it clear that from manufacturing to global freight and delivery, there's strong demand for faster, more agile operations. Despite its devastating consequences, COVID-19 actually showed the progress that has been made, as well as the next steps. Calls for radically new technology are often not as loud as calls for faster penetration of existing technology or, more commonly, recognition of the need for a new mindset. Let's take a look at four important examples of how supply chain technology will be shaped by this pandemic.

1. First Mile

Nearly any shipment, whether international, domestic, or last-mile delivery, requires the services of a truck. In non-COVID times, this is one of the most expensive parts of global shipping, primarily due to the expensive labor costs involved: safety regulations require down-time for drivers in order to ensure alertness, slowing down long-haul trucking or requiring multiple drivers. The one-two punch of electric vehicles to save on fuel costs, as well as the adoption of autonomous driving technology, can introduce radical efficiency to the shipping industry.

Since most trucking miles are driven on interstate highways, which is less challenging for autonomous trucking, this has already been a focus, with companies like China-backed TuSimple or even Google's Waymo active in this space. However, during the outbreak, the barrier wasn't cost, it was simply the pandemic risk. Zooming out, autonomous vehicles can present critical supply chain resilience. This might go some way in explaining a $100 million dollar round raised in late April by Inceptio, a Chinese autonomous trucking company.

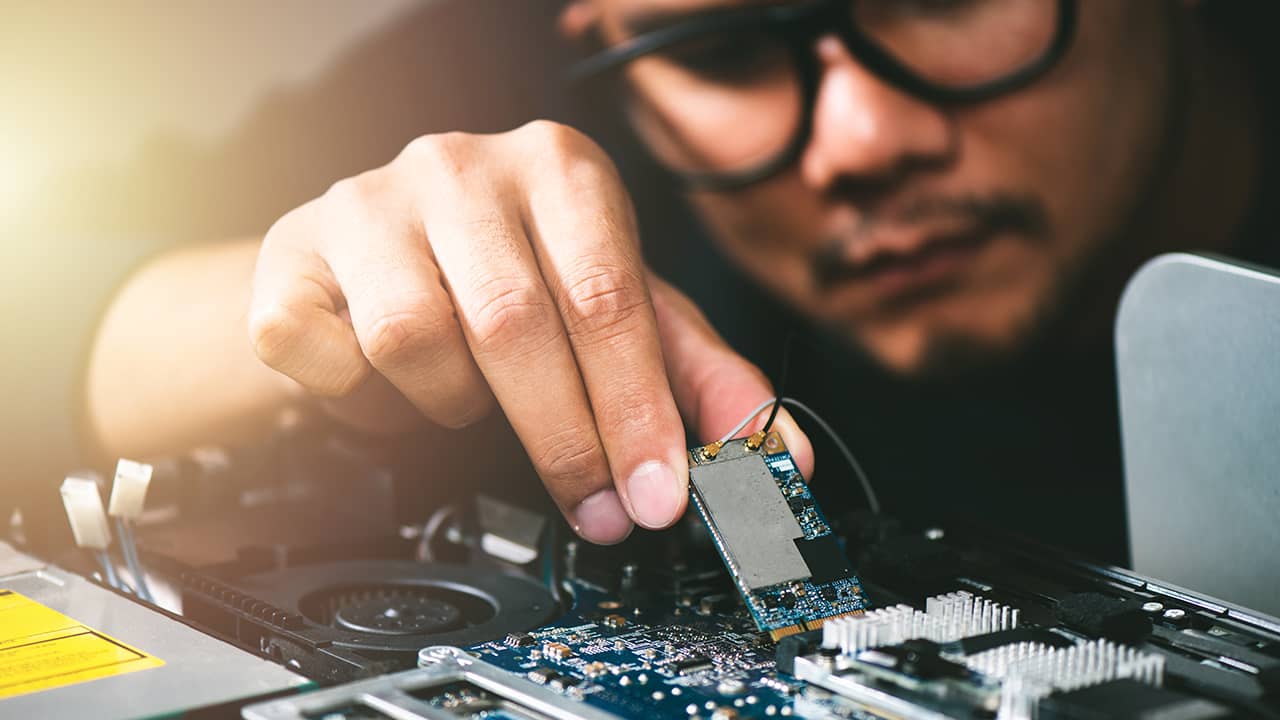

2. Direct-to-Consumer Manufacturing Agility

Over the last few years, there's been a groundswell in direct-to-consumer sales, with companies like Warby Parker and Casper owning the entire manufacturing, logistics, and sometimes, sales for a bespoke product. Behind the trend lies two simple drivers. First, it's easier than ever to reach targeted audiences, either through demand aggregators, like Amazon, or through a company's own website. Second, it's easier than ever to tap into companies like Alibaba, Sourcify, and yes, Freightos.com, to manufacture anything.

This makes small businesses infinitely more agile than the juggernauts, explaining the $1billion acquisition of Dollar Shave Club by Unilever. During the pandemic, this fact became even more apparent. On Freightos.com, shipments to Amazon dropped by 50% when non-essential product sales were halted. But within a week, they had increased by 25%, driven in part by the ability of many importers to suddenly source essential goods instead of their day-to-day business. The fashion industry has been shifting towards Fast Fashion – rapid development, sourcing, and sales – for years but this will accelerate in a post-COVID-19 reality. Beyond process changes, this trend will drive more 3D printing, which allows faster prototyping, as well as innovation in robotics in the manufacturing space.

In the food and beverage business, Trellis developed a food intelligence platform enabling forecasting and optimization of crop production, supply chain fluctuations and market trends.

For international freight, flexibility will remain the byword; the need to rapidly shift import activity from one country to another or even to change the course of a shipment in mid-process if, say, an airport is closed down due to a pandemic, will be key.

"Access to global trade now ranks up there with water, electricity, and internet in the modern Maslowian hierarchy"

3. Capacity Management

Air cargo was pushed to its limit this year. The combination of capacity drops due to fewer passenger flights, with strong demand for urgent goods, led to skyrocketing prices. However, airplane capacity is an issue that plagues the industry on a regular basis. The average load factor - cargo capacity actually utilized - shockingly hovers in the 50% range. In other words, half of a plane's space is usually empty. This increases prices and exacts a heavy environmental toll.

The platform connectivity that has shaped enterpriseB2B sectors like insurance and finance is taking shape through digital air cargo. Companies like WebCargo work together with airlines to digitize available capacity, add a layer of dynamic pricing, and then connect them directly to logistics providers or importers. These steps improve capacity utilization, lower the manual sales and booking time by upwards of three hours per shipment, and, most importantly, lower the end air cargo costs by some 20%, reducing the end cost for consumers. During COVID-19, nascent air cargo eBookings spiked initially, leveraging this new technology, until the stressors pushed the industry too far. However, it made the advantages clear enough that digital cargo procurement will almost certainly surge in a post-COVID-19 era.

4. Last Mile Delivery

With e-commerce delivery clearly more important than ever, the pandemic surfaced two major areas that require a technological solution. The first is the underlying number of companies that can fulfill deliveries, with Amazon owning some half of the entire US e-commerce market. This has prompted Amazon to build up its own delivery infrastructure. However, even before COVID-19, that still meant that half of all deliveries were fulfilled by other companies. The outbreak scare for companies over-relying on Amazon fulfillment is unlikely to be forgotten quickly. Here enter companies like Shopify, which announced a massive fulfillment investment last year and continued with a $450million robotics acquisition last September. Other companies, like ShipBob, are also playing a role in letting any business, Amazon seller or not, manage deliveries. Finally, SaaS companies like Bringg offer subscribeware to manage internal delivery fleets, which further decreases external dependencies.

On the hardware side, COVID-19 also showed that scalable and autonomous delivery is critical. For fulfillment centers, for resilience and sanitary purposes, companies like Fabric can play a huge role in democratizing last-mile fulfillment preparation. Meanwhile, on the delivery front, empty streets and fewer drivers helped cut through red tape and accelerate adoption of drone delivery, like Maana Aero's aerial drone delivery of medical supplies in Ireland.

While the pandemic introduced some major obstacles, chiefly the ability to maintain agile and resilient supply chains from manufacturing to delivery, it also surfaced an important takeaway. Nearly all the technology and new processes required to contend with these types of systematic shocker exist. Moreover, across the entire spectrum of businesses, from one-person e-commerce vendors to Amazon, there already is some degree of adoption. If anything, the crisis may have crystalized just how important faster and broader adoption of these measures are in order to support a world that is increasingly dependent on the ability to get anything anywhere. Because if COVID-19 has made anything clear, it's that ship happens.

Written by: Eytan Buchman (CMO - Freightos.com)

Illustration by: Yaniv Tore

This article was first published as "Chain Gang" in Innovation Insider. Reproduced with kind permission from OurCrowd.

UOB makes no representation or warranty as to, neither has it independently verified, the accuracy or completeness of the information in this article. Any opinions or predictions reflect the writer's views as at the date of this article and are subject to change without notice.